Article

What To Do if ICE Comes Knocking as an Employer

With a new Presidential administration comes changes. President Donald Trump and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem have made immigration enforcement a priority. As a result, employers have noted an increase in ICE encounters and activity. The following outlines some of the critical rights and obligations employers have in this context.

I-9 Form Requirements and Inspections

One of the forms employers require new hires to fill out is an I-9 form. As of 1986, this has been a requirement for all employees regardless of citizenship status. The form is designed to verify an employee’s identity and authorization to work in the United States. Employers are required to have employees fill out Section 1 of the form on the first day of their employment. Section 2 must be completed by the employer within 3 days of the employee’s first day of work.

Once the form is completed, employers are required to keep it for 3 years after the hire date, or 1 year after termination, whichever is later. Employers must keep these records secure in either paper, microfilm/microfiche, or electronic format.

ICE may choose to audit these forms, but before they do so, they are required to present a Notice of Inspection or “NOI.” An NOI needs to be written and served. Once it is served, the employer has three business days to produce the forms and related documents. Typically, there will be an attached letter specifying the documents ICE wants to review. Unless ICE also presents a valid warrant or subpoena, employers are not required to allow ICE agents to enter non-public areas to review I-9 and inspect related documents (5).

If a company chooses to store their I-9 forms electronically, they must provide access to the electronic I-9 system within 3 days of receiving an NOI. Notably, ICE may request access to electronic systems, but direct access is not mandatory unless authorized by judicial warrant or subpoena. If ICE presents a judicial warrant that explicitly states that they can seize or copy a company’s electronic systems or servers, or access data stored on those systems, then the company must comply with this request (4).

Judicial Warrant vs. Administrative Warrant

ICE may come knocking with one of two different types of warrants: a judicial warrant or an administrative warrant. There are key and crucial differences between the two, and employers should tailor their response accordingly.

First, a judicial warrant is issued and signed by a judge. A judicial warrant is usually greater in scope and mandates compliance. It may allow entry into specific areas or seizure of certain documents or individuals.

Alternatively, and more often, ICE agents will present an administrative warrant. Administrative warrants are typically issued by ICE agents themselves and do not authorize entry into non-public areas or allow for a search/seizure without consent. Employers are not legally required to grant access beyond public areas. Notably, administrative warrants do not compel cooperation in regard to search and seizure. Employers are not obligated to consent to a search of non-public areas without a judicial warrant (1).

However, it is important to note that courts have upheld the validity of administrative warrants in immigration proceedings, stating that the Fourth Amendment permits civil immigration detention due to probable cause determinations made by executive officers rather than neutral magistrates (2).

4th Amendment Implications

In 2020, the Ninth Circuit addressed the Fourth Amendment concerns during ICE encounters. The court focused on the requirement of probable cause for detaining individuals under immigration detainers. The Ninth Circuit held that the Fourth Amendment mandates a prompt probable cause determination by a neutral and detached magistrate to justify continued detention under an immigration detainer. Furthermore, detaining an individual for a civil immigration offense without such a determination constitutes a Fourth Amendment seizure, which must meet constitutional standards. (3) Since then, the second Trump administration has implemented a slew of new immigration policies—some of which have been challenged in court

One such challenge was in Perdomo v. Noem, where a class of plaintiffs sued Kristi Noem in her capacity as Secretary of Homeland Security. In that case, some of the plaintiffs were arrested at a bus stop while waiting for a job pickup, while others were U.S. citizens who were detained and questioned by immigration agents. Plaintiffs asserted that these series of arrests, detentions, and questionings were unlawful and violated their 4th and 5th Amendment rights. The federal district court sided with the plaintiffs, holding that the searches and seizures violated the 4th amendment as they occurred not based on reasonable suspicion, but rather based solely on factors like race, language, location, and occupation. The Court also found that denying detainees access to counsel violated their Fifth Amendment due process rights (9). Kristi Noem’s application for a stay of that decision pending a further decision on appeal by the 10th Circuit was granted by the U.S. Supreme Court in July 2025. (10)

While Perdomo and other cases make their way through the courts, it is crucial for employers to be aware of the Fourth Amendment implications surrounding immigration enforcement in the workplace. The key takeaway for employers is the importance of ensuring that any interaction with immigration authorities complies with existing laws. Being aware of these laws allows employers to understand the extent of their obligations and to maintain the integrity of their workplace, as they choose within the boundaries of the law. In most instances, it is the right of an employer to consent to a search of their property, voluntarily, but it is critical to know when such a search is legally required.

State Cooperation

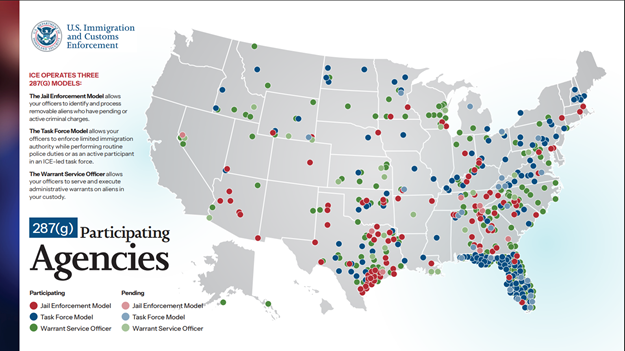

Many Republican leaning states are opting to implement statewide measures to enhance cooperation with ICE. Most prominently, Texas, Indiana, and Arkansas are all considering actions which would mandate sheriff’s departments and local law enforcement to cooperate with ICE. The Texas law would require sheriffs to enter into 287(g) agreements with ICE. The 287(g) Program gives participating state and local law enforcement agencies the authority to identify and process removable aliens with pending or active criminal charges, enforce limited immigration authorities with ICE oversight during routine duties and serve and execute administrative warrants on removable aliens in custody. These agreements would give sheriffs limited authority to act as immigration enforcement agents within their jails or in the community, after receiving ICE training. Notably, participating departments do not have the full scope and authority of ICE agents; although they must undergo ICE training to participate, they can only perform limited immigration enforcement under ICE supervision (6).

Currently, ICE operates three different 287(g) models: The Jail Enforcement Model, The Task Force Model, and The Warrant Service Model. The attached map from ice.gov shows just how many of these programs are currently operating within the United States. The Texas law would mandate these programs for all sheriff’s departments within Texas (6).

Conversely, California is an example of a state that restricts ICE’s increased access to workplaces. Under California law, employers are prohibited from voluntarily allowing immigration enforcement agents to enter non-public areas of a workplace without a judicial warrant. This law effectively prohibits voluntary compliance with administrative warrants within the state and imposes penalties on employers who do so (7). The California law also prohibits employers from voluntarily providing ICE access to employee records without a subpoena or judicial warrant, with certain exceptions for I-9 forms and related documents. (8).

Other states, such as New York and New Jersey, have issued guidance reminding employers that every resident and visitor to the state has rights regardless of their citizenship or immigration status and providing them with information regarding their rights and responsibilities as employers when interacting with immigration enforcement officers. (11)

Concluding Thoughts

In the coming months, it will be crucial for employers in every sector to keep an eye on changing federal and state regulations regarding the enforcement of immigration laws. Immigration policy is becoming increasingly political, and it is important to tune out the noise and keep track of the changes that will most affect your workforce. Know your rights when ICE comes knocking, prepare in advance for any possible interaction with ICE, so that both you and your ‘front-line’ employees know what to do, including the creation of appropriate protocols, policies, and training your staff.

Sources:

1. Ramon v. Short, 2020 MT 69 (Supreme Court of Montana)

2. Aguilar v. U.S. Immigration & Customs Enf't Chi. Field Office, 346 F. Supp. 3d 1174 (N.D. Ill. 2018)

3. Gonzalez v. U.S. Immigration & Customs Enf’t, 975 F.3d 788 (9th Cir. 2020)

4. 8 C.F.R. § 274a.2(b)(2)(ii)

5. https://www.ice.gov/factsheets/I-9-inspection and 8 C.F.R. §274a.2(a)(2)(ii)

7. Cal Gov Code § 7285.1

8. Cal Gov Code § 7285.2

9. Perdomo v. Noem, 2025 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 134409

10. Perdomo v. Noem, 606 U. S. ____ (September 8, 2025)

11.https://ag.ny.gov/immigrants-rights/ice-workplace; https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/njnewamericans/newcomers/docs/KnowYourRights-Bus_en.pdf